A quick internet search reveals a mind-boggling amount of content on leadership but perhaps Brené Brown, in her bestselling book “Dare to Lead,” lays out leadership most succinctly. Ms. Brown defines a leader as “anyone who takes responsibility for finding the potential in people and processes, and who has the courage to develop that potential.” Not to discount vision and strategy, but this may well be the core task of leadership.

Sounds easy enough, but how does one develop the potential in others? For starters, leaders must have empathy and emotional intelligence, both of which derive from healthy self-awareness and self-awareness must be developed; it is not innate. In Poor Richard’s Almanac, Ben Franklin said “there are three things extremely hard: steel, a diamond and to know one’s self.” Rudyard Kipling, also recognizing the difficulty in knowing oneself, encourages self-awareness in his timeless poem “IF,” which begins:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise:

Are business leaders self-aware? A Harvard Business Review article estimates that no more than 10% to 15% of people are truly self-aware yet most people would claim to be. Business leaders, especially more senior managers with experience and power, may be even more lacking in self-awareness, despite its importance to good leadership. Yet, its self-awareness that helps one to: (i) understand his/her own passions, interests and personality; (ii) know what he/she doesn’t know; (iii) better understand how he/she is perceived and his/her effects on other people; and (iv) become more inquisitive.

Consider a situation at Harvard Business School. After 50 years of accepting women who entered with comparable grades and test scores to male students, women remained underrepresented among Baker Scholars, the top five percent of their class. HBS Dean Nitin Nohria, appointed in 2010, and his colleagues sought to change this. Was it “second-generation gender bias,” i.e., not outright or explicit discrimination but implicit discrimination based on cultural and historical assumptions about conducting business and individual roles?

At HBS, the case method is used exclusively and class participation accounts for 50% of student grades. So, were women not participating? Were their class comments not insightful? No. To address the issue, the school installed a scribe and, in turn, recording systems in every classroom. Faculty members became more aware of their calling patterns and began making a more determined effort to include all students in class discussions. While this may seem intuitive, carefully selected faculty members who arrived at the school with outstanding credentials, distinguished track records as business leaders and open minds, could still fall prey to second-generation gender bias. In other words, some faculty members were not fully self-aware.

It took time, but in 2013, the percentage of women receiving the Baker-Scholar distinction rose to a level commensurate with their percentage of the student population – and it has remained there. This was not about diversity – HBS had been matriculating women for decades – but it was about inclusion. In the words of Vernā Myers, diversity consultant and author, “Women were invited to the party but weren’t invited to dance.”

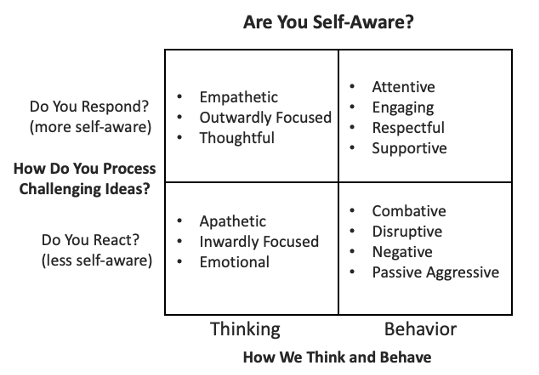

Business leaders need to hear all voices, not simply the louder ones, and avoid giving too much credence to certain managers or groups. Again, from Kipling’s poem, “If all men count with you but none too much.” Leaders, – nay, all of us – need to respond rather than react to what we see and hear. As the Self-Awareness chart below suggests, reacting may trigger emotional and self-oriented thinking and, worse, detrimental behavior. Who hasn’t, in a moment of passion, reacted and said something they would later regret? In contrast, a thoughtful response will likely reveal a more outward focus, empathy and respect for those being addressed. Those who respond have agency while those who react generally do not.

All of us have seen conversations where participants react with opinionated and emotional rants, just as all of us have seen people withdraw from a conversation due to someone reacting with negative or judgmental comments, and no one benefits. What if we all learned to respond to a challenging idea, even a political idea, with nonjudgmental questions such as: can we explore that idea? can you take me on your journey? or my point of view is different, can you help me understand how you arrived at yours? Questions won’t stop every rant, but they do engage people, encourage discourse, enhance understanding and unlock good thinking. What’s more, questions lead to greater rapport and, in turn, build trust.

As a business leader, or even a meeting facilitator or chair, a question represents one of the best tools for responding and drawing out quieter voices. Effective leaders often begin a discussion by stating an objective, asking for ideas and then actively listening, i.e., not simply formulating what to say and waiting to talk. Questions allow leaders to engage a group or a specific individual. Moreover, the use of questions can help keep one’s personal biases, explicit or implicit, in check.

If Brené Brown is correct, business leaders have an obligation to explore the potential of all ideas. Some will doubtless warrant more consideration than others but, as the case method teaches, there is seldom one right answer and monolithic thinking often leads to poor decisions. Leaders must learn to pause, reflect and respond – and teach others to do so as well. Leaders must develop self-awareness and learn to hear and engage all voices.

To be clear, self-awareness isn’t required to ask nonleading and nonjudgmental questions; forethought and preparation are. Nor is it required to listen effectively to people’s answers. But knowing oneself and one’s effect on others will prove pivotal to encouraging participation, drawing out ideas, finding the best way forward and building real consensus. And knowing oneself…

Again, from “IF:”

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much

If leaders want to take responsibility for finding the potential in people and processes, and develop that potential, they must learn to listen, to give every voice its audience and thoughtfully respond to what they see and hear. If leaders want to have a meaningful and lasting impact on the people around them and the businesses they serve, they must engage in supportive and respectful behavior. If leaders want to avoid second-generation bias of any type, and if they want to become truly effective leaders, they must first know themselves.

If…

Footnote:

For information on second-generation gender bias, read “Women Rising: The Unseen Barriers by Herminia Ibarra, Robin J. Ely, and Deborah M. Kolb, Harvard Business Review, September 2013.

Acquiring companies cannot eliminate risk but they can mitigate it. Performing sensitivity analyses and assigning probabilities to potential outcomes will lead to a more robust estimation of future value. Moreover, this effort will help forestall or altogether avoid future problems. At the very least, it will lead to a better understanding of the challenges of forming the new company.

Acquiring companies cannot eliminate risk but they can mitigate it. Performing sensitivity analyses and assigning probabilities to potential outcomes will lead to a more robust estimation of future value. Moreover, this effort will help forestall or altogether avoid future problems. At the very least, it will lead to a better understanding of the challenges of forming the new company.